Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

The most remarkable thing about the shooting of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson on a New York street in early December was the reaction. Most comments on social media blew past the horror of the killing to express outrage at our medical insurance system. Everyone, it seemed, had a story of a family member’s being denied coverage for serious problems. These reactions were doubly surprising since we’d just been through an election where the issue barely came up. Yes, there was vague talk—recall Trump’s “concepts of a plan”—about expanding or cutting Medicare, Medicaid, and Obamacare, but directed rage against companies like UnitedHealthcare had been nowhere to be seen.

As a historian who has written about folk heroes, I can see how Luigi Mangione—who was arrested last week and indicted Tuesday on charges that include first-degree murder—has personalized a big, amorphous issue, crystallizing it into a clear moral parable. Suddenly it was no longer the language of in network, out of network, annual deductibles. It was the language of heroes and villains, the shooter as cold-blooded killer or culture warrior, Thompson as money-grubbing CEO bleeding Americans dry or good family man bleeding out on the street. Overnight, a faceless corporation, made invisible by arcane laws and corporate jargon, stood exposed, naked in its greed.

We like to think of American history as orderly, democratic, fair. Actually, violent episodes often drag issues people would rather avoid into the public forum. For decades, politicians contrived compromises to keep the issue of slavery from exploding, but Nat Turner’s bloody rebellion in 1831 jolted Southerners into an awareness that slaves might wish to cut their throats. A wave of repression followed. About 30 years later, John Brown’s bloody plot to foment a slave revolt awakened many Northerners’ rage against the “slaveocracy,” ratcheting up the momentum toward civil war. Or, to take a different issue, workers’ rights: A strike that had simmered in the Colorado coalfields for a year exploded in April 1914 with “Bloody Ludlow,” when state guards torched a miners tent colony, killing 11 women and children. Public fury, congressional investigations, and presidential intervention followed.

But the example from history that strikes me most forcibly comes from the Great Depression. Unlike Mangione, John Dillinger was no scion of a wealthy family. He did not attend an Ivy League college or even finish high school, and he certainly never wrote a manifesto or intended to make a political statement. But between fall 1933 and summer 1934, he embarked on a series of bank robberies that helped galvanize Americans’ hatred of financial institutions. Just as Thompson’s shooter has called attention to the predations of insurance companies, Dillinger was a lightning rod for the public’s hatred of banks.

Dillinger had spent most of his adult life behind bars for a botched stickup, and by the time he got out of Indiana State Prison, just months after Franklin Roosevelt took office, he was 30 years old, with no job prospects. But he had learned a lot about robbery from his fellow inmates, and soon he broke several of them out of prison and began a yearlong crime spree, first robbing police armories for weapons, then picking off over a score of small-town banks across the Midwest. Along the way, a dozen citizens lost their lives.

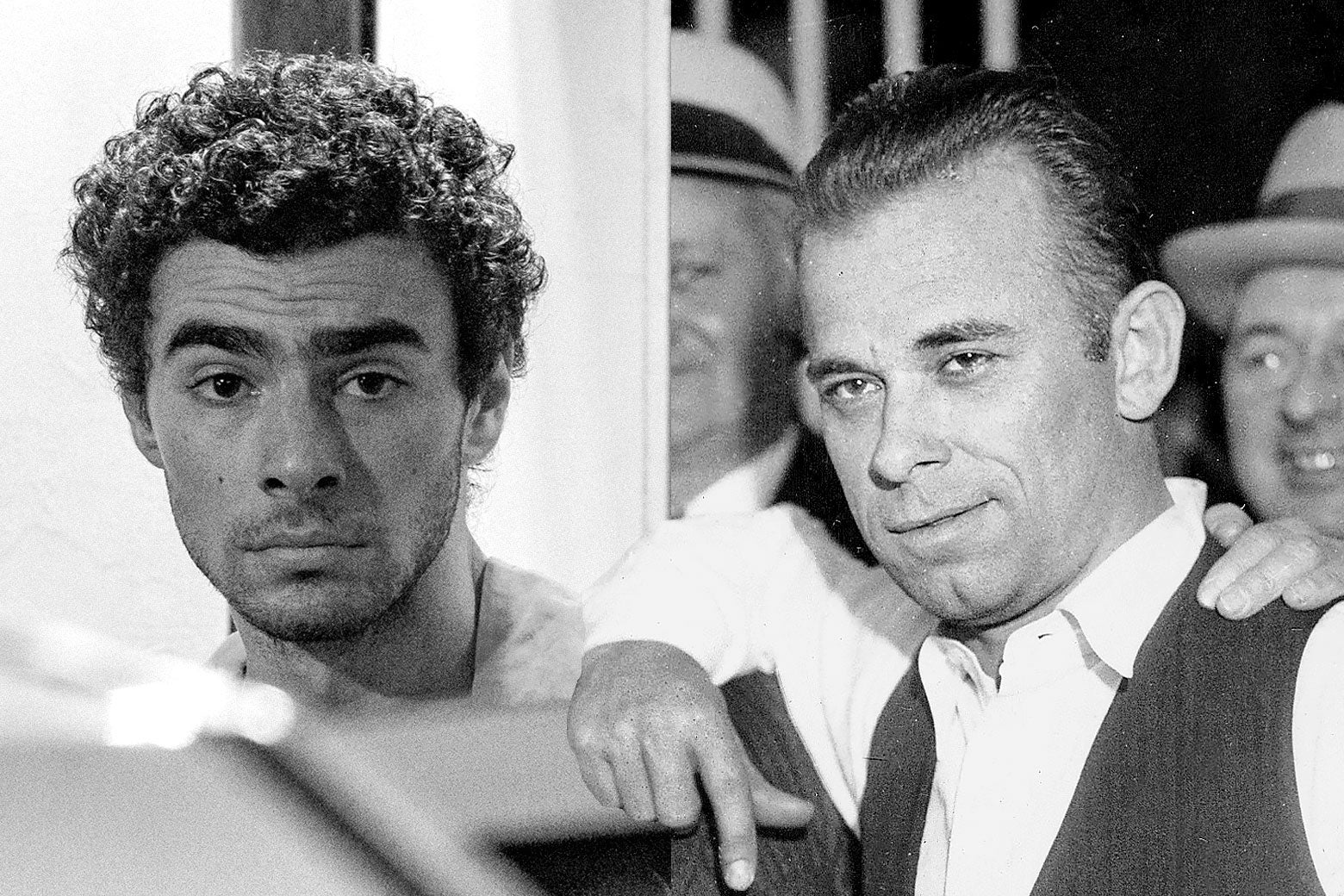

The “Dillinger gang,” as the newspapers called the group, included a rotating band of half a dozen felons and their girlfriends. They went on the lam to Chicago, Florida, and Arizona, and points in between. In early 1934, the entire crew was arrested in Tucson, and Dillinger was extradited to Crown Point, Indiana, to stand trial for the murder of a police officer. There is a famous photo of Dillinger, smiling, handsome, arm in arm with the local sheriff and district attorney. A month later, he broke out of the Crown Point jail with a wooden gun. In the spring, more screaming headlines detailed his miraculous escape from the FBI in northern Wisconsin, with one journalist dubbing him “the Houdini of the bank robbers.”

Dillinger was one of a handful of celebrity criminals in this era: Bonnie and Clyde, Machine Gun Kelly, Ma Barker’s gang. Americans were horrified at their lawlessness and violence. They were also mesmerized by it. And they were especially taken with banks’ being the targets of their depredations. By the time Dillinger died at the hands of the FBI on the streets of Chicago on July 22, 1934, roughly 10,000 U.S. banks had closed their doors, bankrupt, the savings of millions of citizens and businesses evaporated. Banks and bankers were often blamed for the economic cataclysm of the Great Depression, when, during Dillinger’s wild year, more than 25 percent of Americans were unemployed.

“If he robs a bank, what of it,” Mrs. W.B. Grant of Butler, Tennessee, wrote of Dillinger to first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. “Hasn’t most of the bankers themselves been crooked, and that is how they became wealthy, by cheating the honest man.” This theme was repeated over and over again in the public’s assessments of Dillinger. Joseph Edwards wrote President Franklin Roosevelt to assert that Dillinger robbed banks merely from the outside; bankers themselves robbed them from the inside. W. Guyer Fisher wrote about businessmen who “fleeced the rank and file out of … their hard earned cash,” calling them “wholesale thieves that use a sharp pencil” to rob a bank or steal a public utility. Another citizen asked the president when the government would go after “the real racketeers,” and yet another urged the feds to pursue the “legalized robbers” who pulled their heists “under cover of the law.”

In the public imagination, the conception of Dillinger and of Thompson’s shooter, already infused with explosive violence, easily takes on libidinal elements. Unleashed desire for things like vengeance readily leak over into other id fantasies. Social media posts have repeatedly called Mangione “hot,” dwelled on his face and body, transformed him into an object of sexual desire. The same was true of Dillinger. Americans whispered stories of his sexual potency and libidinous liaisons, less with condemnation than with fascination. He and Thompson’s shooter acted on violent impulses others felt but dared not replicate; it was not a long leap to imagining them as sexually liberated too.

There is a long tradition of “social bandit” legends in England, America, and other countries. Sometimes the outlaw is depicted as a Robin Hood figure, taking from the rich and giving to the poor. Equally often, the hero of these stories is not particularly altruistic, just aggrieved, like many of his countrymen, against his “social betters” or haughty institutions. In that sense, the CEO shooters, like the John Dillingers of the world, become legendary figures, not necessarily virtuous, but social avengers. The same, by the way, was true of Nat Turner and John Brown—bloodthirsty monsters for some, avenging angels for others.

I’m guessing that the rage evoked by Thompson’s killing is emblematic of something larger. We kept hearing over and over during the election that voters’ greatest concern was the economy. But maybe pundits interpreted that too narrowly to mean inflation, merely the cost of eggs. Maybe the economy and inflation were catchalls for deeper anxieties, barely articulated—health care costs; the price of pre-K through college education; the death, for so many, of the American dream of homeownership; the precarity of jobs in an age of gig work, side hustles, and artificial intelligence; all this in contrast to the growing concentration of wealth.

The shooting of Brian Thompson tapped into something deep. This is not the first time in American history, nor will it be the last, that a seemingly random act of violence has revealed repressed rage.