Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

It’s been a busy week. It’s about to get busier. On Friday the Supreme Court will hear arguments in the TikTok ban case. Also Friday, Justice Juan Merchan in Manhattan is set to sentence President-elect Donald Trump in the hush money trial. Trump has appealed that matter to the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, Judge Aileen Cannon, in Florida, blocked the release of special counsel Jack Smith’s final report on the two investigations that led to federal felony charges against Trump. Justice Samuel Alito chatted with the president-elect over the phone Tuesday over a Trump transition HR matter, hours before the court was asked to weigh in on the Manhattan sentencing case. On Amicus Plus, Dahlia Lithwick spoke to Andrew Weissmann, co-host of the podcast Prosecuting Donald Trump (which has been newly christened Main Justice) and a legal analyst for NBC/MSNBC. His memoir about working on the Robert Mueller special counsel investigation, Where Law Ends: Inside the Mueller Investigation, was a New York Times bestseller. Their conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Dahlia Lithwick: Andrew, you and I spoke on your podcast—it feels like a hundred years ago, but really just a couple of weeks ago—about the big existential question of why the law so utterly failed to keep up with Trump and MAGA and the insurrection. Here we are, just two weeks later, and we’re bearing witness to a concerted effort to not simply erase Trump’s criminal liability by stopping the sentencing that makes him a felon but actually erase the documents and the reports and the testimony from the historical record itself, in terms of special counsel Jack Smith’s report. That feels like a shift to me, that this is not just making the cases go away; this is an attempt to make the actual underlying evidence and testimony go away.

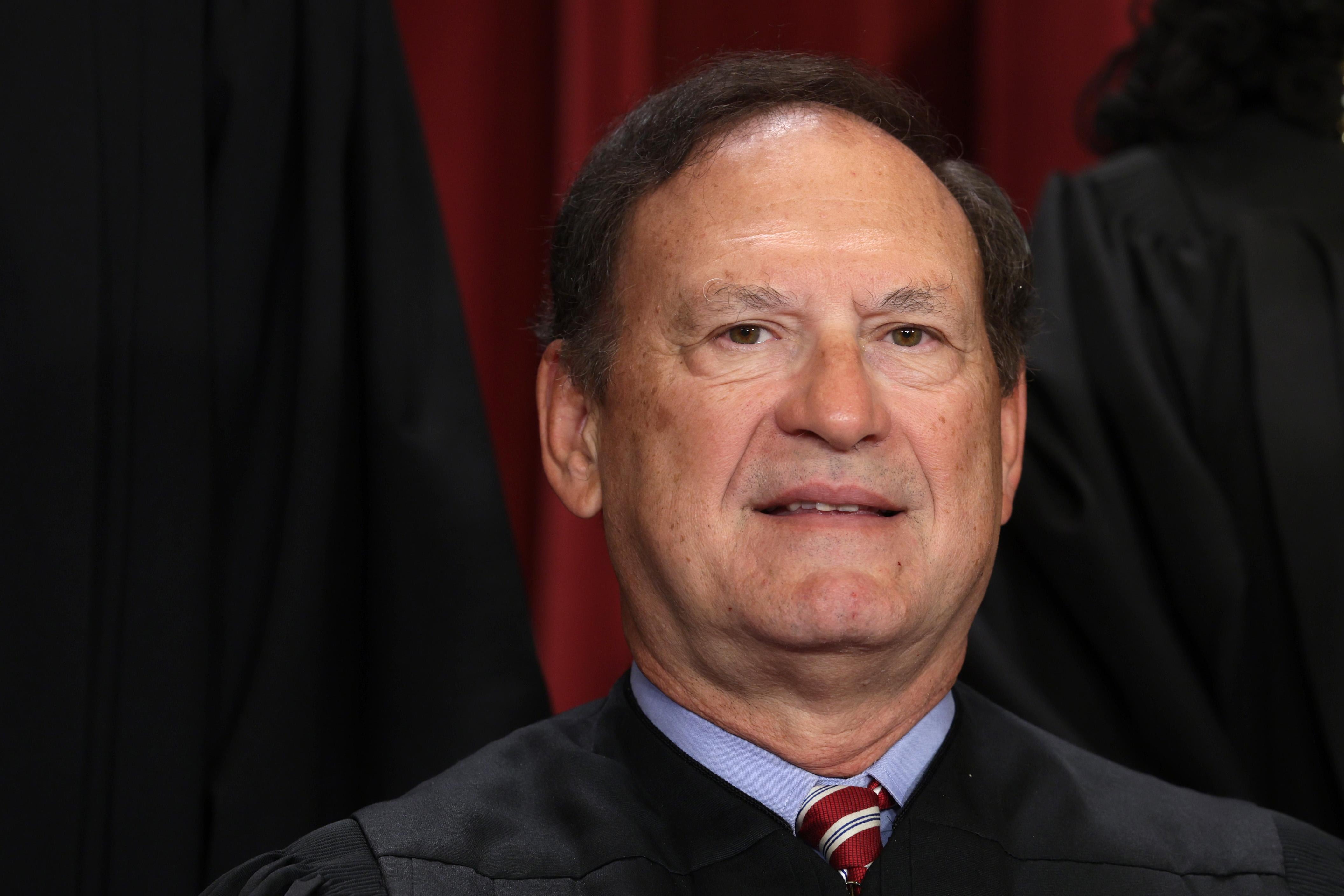

Andrew Weissman: I do think that we’re in a new terrain. We’re seeing some of this play out in the judicial branch, where we see judges like Aileen Cannon, in Florida, act pretty outrageously, and Justice Samuel Alito on the phone to the president-elect the day before Trump’s outrageous appeal landed at the high court. Alito’s claim that he didn’t expect that there would be any of this litigation in the Supreme Court is just not credible, in my opinion.

With respect to the dissemination of Smith’s reports, this is a complicated issue because the normal rule is that when somebody’s not charged, you don’t hold a press conference and talk about all of your views about the person. That was the Jim Comey problem with respect to Hillary Clinton; that was the platonic ideal of what you’re not supposed to do. When it comes to a report by the special counsel, there is an exception—it’s authorized by the attorney general regulations—and there are precautions that can be taken when there is grand jury material or when there is a true pending case against somebody who is being named in the report.

It’s important for the public record and for history. There is a “Facts matter” component to this. It should be made public so it’s something that people can see and evaluate. Even if we’re in a place in our history right now where that doesn’t seem to be paramount for a lot of people, it’s still important for the public record.

I should note what Attorney General Merrick Garland intends to do with respect to the Mar-a-Lago volume of the report, which would not be public but would go to the legislative branch. In other words, there would be majority and minority members, Democrats and Republicans, who would get it, so it would make it harder for it to disappear on Jan. 20 in the next administration, even if there were an effort to do that.

The other thing that Garland could do, and I was surprised he hasn’t, is file it with the court so that the full report is in front of, for instance, the chief judge of the Washington court. They could also have filed it with the 11th Circuit so that the circuit could see the full report. It’s a way to use the courts as a repository, because the courts are not in the control of (or are not supposed to be in the control of) the executive branch. This was something we were very cognizant of when I was in the Mueller investigation: We all thought we could be fired at any moment, and we wrote fairly fulsome search warrants and other material for the courts, understanding that this was a way of preserving—to the extent we could, and within the law—what we were doing.

I do want to talk some more about this phone call between Alito and Trump, apparently discussing a former Alito clerk who’s going to have some position in the next Trump administration. Except … oops! He already had a position in the last Trump administration. He worked for Bill Barr. I’m really struck by one fact, which is that Comey later cited to that meeting on the Tarmac between Loretta Lynch and Bill Clinton as the moment in which the wheels had come off and that public confidence was so eroded by this brief meeting between the former president and the then attorney general that Comey had to behave as he behaved.

Here we are now, not that many years later, and we’re just having casual ex parte conversations with a justice who, as you said, claims—not very credibly—that he didn’t know there was a case being filed at the court. He says he had no idea it was coming and therefore had no sense that there was anything improper about a little staffing chitchat. This comes less than two weeks after the chief justice’s warning to all of us who criticize the courts in his end-of-year report. And that report included the line “The federal courts must do their part to preserve the public’s confidence in our institution.”

I’m really stunned at how far we have come: from Comey’s statement after the Lynch–Clinton Tarmac meeting that this is intolerable, to this casual chat between a party to a proceeding that is now pending at the court and one of the justices, who, by the way, also flew some flags. It’s amazing to me how far we have come in terms of institutions failing to protect themselves.

I worry not just that the erosion of confidence in institutions is coming from inside the house but also that the house doesn’t care.

It’s worth remembering that, with respect to Lynch, there were other people present for that meeting. This was not a one-on-one. There was the Secret Service; there was her husband. Also, you hardly needed to meet with Clinton to know that he would not want to see his spouse prosecuted. But it’s important too to remember what Lynch did in response to that, which was to say, “Given the appearance of impropriety, I’m going to accept the recommendation of the career people in whatever they decide to do.” So she took a step to assure people, given the alleged appearance of impropriety.

With respect to the Supreme Court, I couldn’t agree with you more: The chief justice has a problem. There is just no oversight going on, and Alito’s comment—that with respect to Trump, he was unaware that any of this was going to come up to the court—is just not credible. The day before this phone call, Lawrence O’Donnell and I were on air, talking about how these appeals were going to end up in the Supreme Court, and that’s true, obviously, with respect to the sentencing that is now before the court. So the idea that Alito was not aware of that, and that he would then pick up the phone on something as ministerial as a résumé check, and then also as if the president-elect, who is so busy being president-elect that he can’t go to his own sentencing—even though the judge said no jail time, no fine whatsoever—but can take time to talk to Alito about somebody he’s going to give the job to anyway? All of this is so fanciful and outrageous, and the idea that the eight justices wouldn’t sit down with Alito and say “You need to recuse” is just unbelievable. It makes a mockery of the so-called ethics rules that they put in place but that there’s no mechanism to enforce.