Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

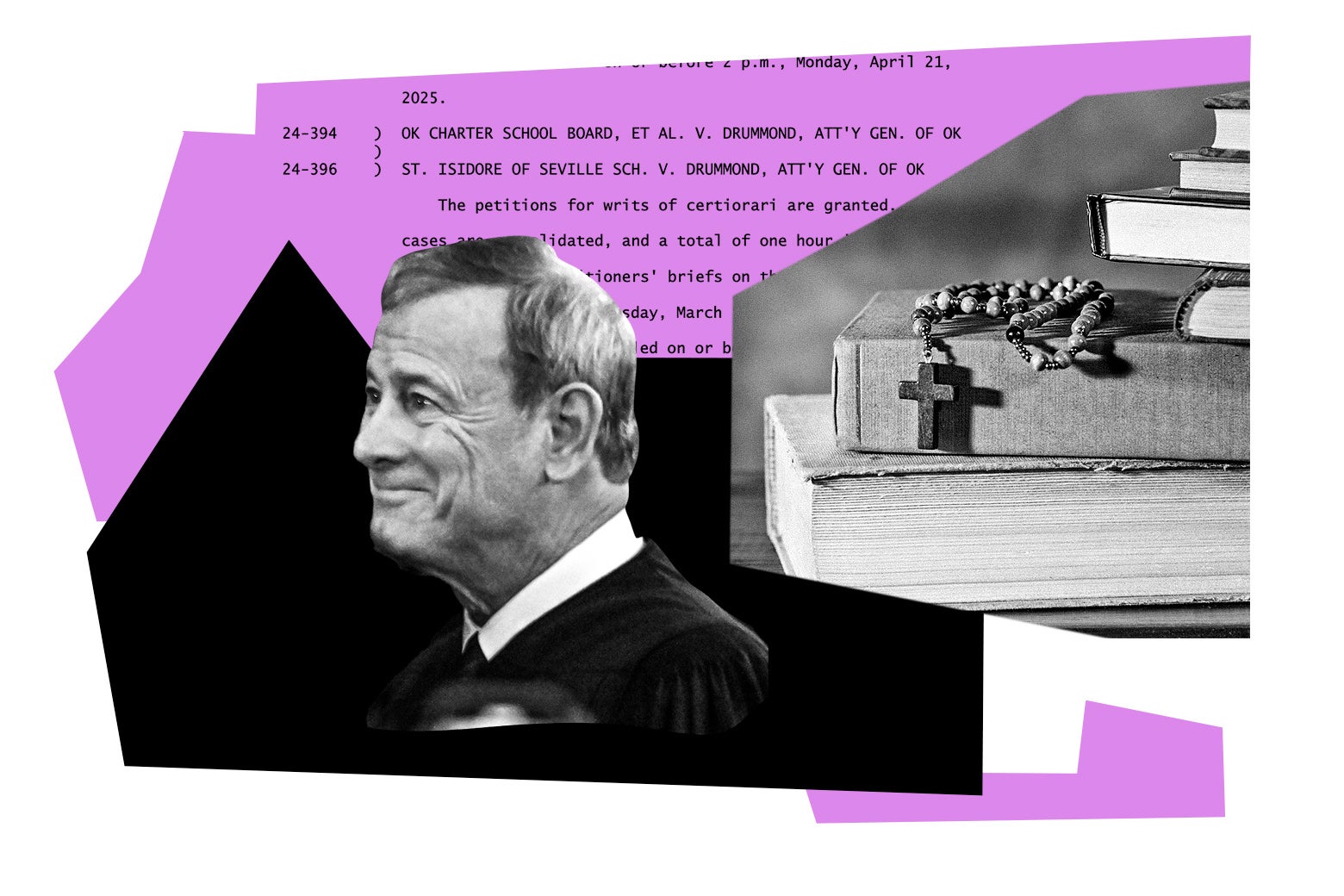

In 2023 a new online-only public charter school opened in Oklahoma. But there was something unusual, and seemingly unconstitutional, about this school: It is Catholic. According to the state’s constitution, as well as historical interpretations of the U.S. Constitution’s establishment clause, public funds should not flow to sectarian institutions for sectarian purposes. Citing these concerns, the state attorney general stopped the funding. However, the school and the statewide charter school board sued, arguing that depriving the school of public funding was, in effect, a violation of its religious freedom. The Oklahoma Supreme Court agreed with the state of Oklahoma and blocked the opening of St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, but recently, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

The school’s argument is essentially that the establishment clause, when interpreted this way, violates the free exercise clause. This follows a series of recent cases in which the Roberts court has protected free exercise of religion, even at the expense of church–state separation. The erosion of the establishment clause is important, but not necessarily because the so-called wall of separation is itself so valuable or possible. The separation of church and state matters because it can help protect public things (and, as the founders argued, churches too). But this case raises even more fundamental questions. What is a public school? And what makes it public?

For a school without any students or buildings, St. Isidore’s influence on U.S. education could be cataclysmic. The school’s features signal privatization: It is a remote Catholic charter school. Yet, St. Isidore’s slogan is “Available to all students in Oklahoma.” The school aims to redefine the public in public education. The FAQs on the school’s website take pains to distinguish charter schools from public ones, emphasizing that the school merely “contracts with” the state (or did, until the Oklahoma Statewide Charter School Board rescinded the contract last June, following the state Supreme Court’s decision). Among the questions are “Would the government assign children to attend St. Isidore?” (“No”) and “Is St. Isidore an arm of the government?” (also “No”). The school’s aims are crystal clear: “Although Oklahoma’s Charter Schools Act labels charter schools ‘public,’ that designation simply means that charter schools are free to all students and supported by State funds—not that privately operated charter schools are the same as government run, district public schools.”

St. Isidore is using the courts to further its own conservative Catholic agenda, but that is not all. It is advancing the privatization of public education—charter schools, school choice, parental rights, and remote learning—to claim it as a public institution and also not. Further, post-COVID booms in virtual schooling and charter schools, along with the anti-DEI and anti-trans pushes for school choice, have created a recipe for a new kind of public school. This is not a neighborhood school; students don’t have to leave their houses. This is something else entirely.

In this view, publicness is not about deliberation and collective action; it represents siloed, immovable identities each getting their piece of the pie.

The conservative Christian legal advocacy group Alliance Defending Freedom has taken the case, adding it to a roster of clients including a cake baker who refused to make a wedding cake for a gay couple and a website designer who feared that her free speech would be violated if anyone required her to make a wedding website for a same-sex couple (although none had yet). The ADF has spent much of its time and considerable resources lately drafting and supporting anti-trans legislation and opposing protections for gender-affirming care. Oklahoma State Superintendent of Public Instruction Ryan Walters has also supported the school, even filing an amicus brief. Walters made headlines last summer for ordering compulsory use of the Bible as a teaching tool in fifth through 12th grades, seemingly establishing conservative Christianity in Oklahoma public schools. (Legal challenges, alleging establishment clause violations, are ongoing.)

It should not be surprising that such a convoluted tangle of religion and politics has landed in public schools. Throughout American history, the school has been a frequent battleground for church-state issues. As recent Supreme Court cases have continued to shift jurisprudence around religious freedom, the school has once again become central. In 2022 SCOTUS decided two key cases: Kennedy v. Bremerton and Carson v. Makin. Both of these set the stage for this case.

In Kennedy, the court found that a public-school football coach could pray publicly, even apparently leading students in (voluntary) prayer, while representing the school. When they faced establishment clause concerns, Kennedy and his attorneys successfully argued that disallowing him from leading these public prayer circles—and declining to renew his contract when he refused to stop—violated his right to exercise his religion freely. Carson dealt with a policy in Maine in which, in areas where public schools are unavailable, the state offers to pay student tuition for private “nonsectarian” schools. Some parents wanted those funds to go to sectarian institutions as well. The Supreme Court agreed that the “nonsectarian” requirement was unfair. Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the majority that governments cannot “exclude religious persons from the enjoyment of public benefits on the basis of their anticipated religious use of the benefits.” To discriminate against religious schools—by failing to offer them the same benefit nonsectarian schools receive—violated the free exercise of the religious parents who brought the case.

St. Isidore builds on these cases and attempts to take them a step further. This is a fascinating new chapter in American Catholic history. Catholic schools have long sought to build community through shared physical ritual, often in neighborhoods. Moreover, Catholic schools exist because the earliest form of American public education was Protestant. Catholics were excluded from how “the common” and “public” were framed.

In 1875 Sen. James Blaine proposed a constitutional amendment prohibiting aid to religious (i.e., Catholic) schools. While it failed at the federal level, many states adopted their own no-funding principles amid anti-Catholic nativism against Irish and Italian immigrants. In 1971 the Supreme Court developed the Lemon test, a recently defunct but once quite important metric, finding that using state funds to reimburse Catholic school teachers’ salaries violated the establishment clause. In what would be a truth-is-stranger-than-fiction reversal, the Catholic Church may soon own and operate a public school—because denying it would violate its free exercise of religion.

Church-state separation is worth defending not necessarily because of the principle in and of itself, but because it helps protect public goods. This case shows that the conservative project of dismantling public things is about not simply privatization—diverting public funds into private hands—but, in fact, privatizing the public sphere for its own ideological purposes.