The harrowing history behind 'I'm Still Here'—the film that's captured the world's heart

The Oscar-winning film tells the true story of a former Brazilian lawmaker who was abducted under Latin America’s longest lasting military dictatorship.

On a hot January morning in 1971, plainclothes security agents knocked on the door of the beachfront home of former Brazilian lawmaker Rubens Paiva. Hustled into his car, Paiva was sped away under armed escort and never seen again, leaving his wife and five children to pick up the pieces.

This is the broad plotline of I’m Still Here, the Oscar-winning film set during Brazilian military rule. But rather than dwell on the dictators’ dungeons and the all too visceral horrors of state-sponsored violence, director Walter Salles flips the narrative.

Instead, the film pivots to Paiva’s wife, then widow, Eunice, as she relentlessly presses an obtuse military junta for justice over the next five decades, even as she struggles to provide for a fractured family. It’s an intimate window on Brazil’s collective angst, loss, and resilience.

The backstory is no less harrowing.

The makings of Latin America’s longest lasting military dictatorship

The path to Brazil’s most consequential bout of martial rule began with the country’s thwarted international ambitions following World War II.

Having joined the West in its war on Axis powers, and even dispatched combat troops to Europe, Brazil’s political class was stung by the U.S.’s perceived postwar indifference—not least the refusal to back the Brazilian bid for a seat on the United Nations Security Council.

(How three sisters took down a dictator in the Dominican Republic.)

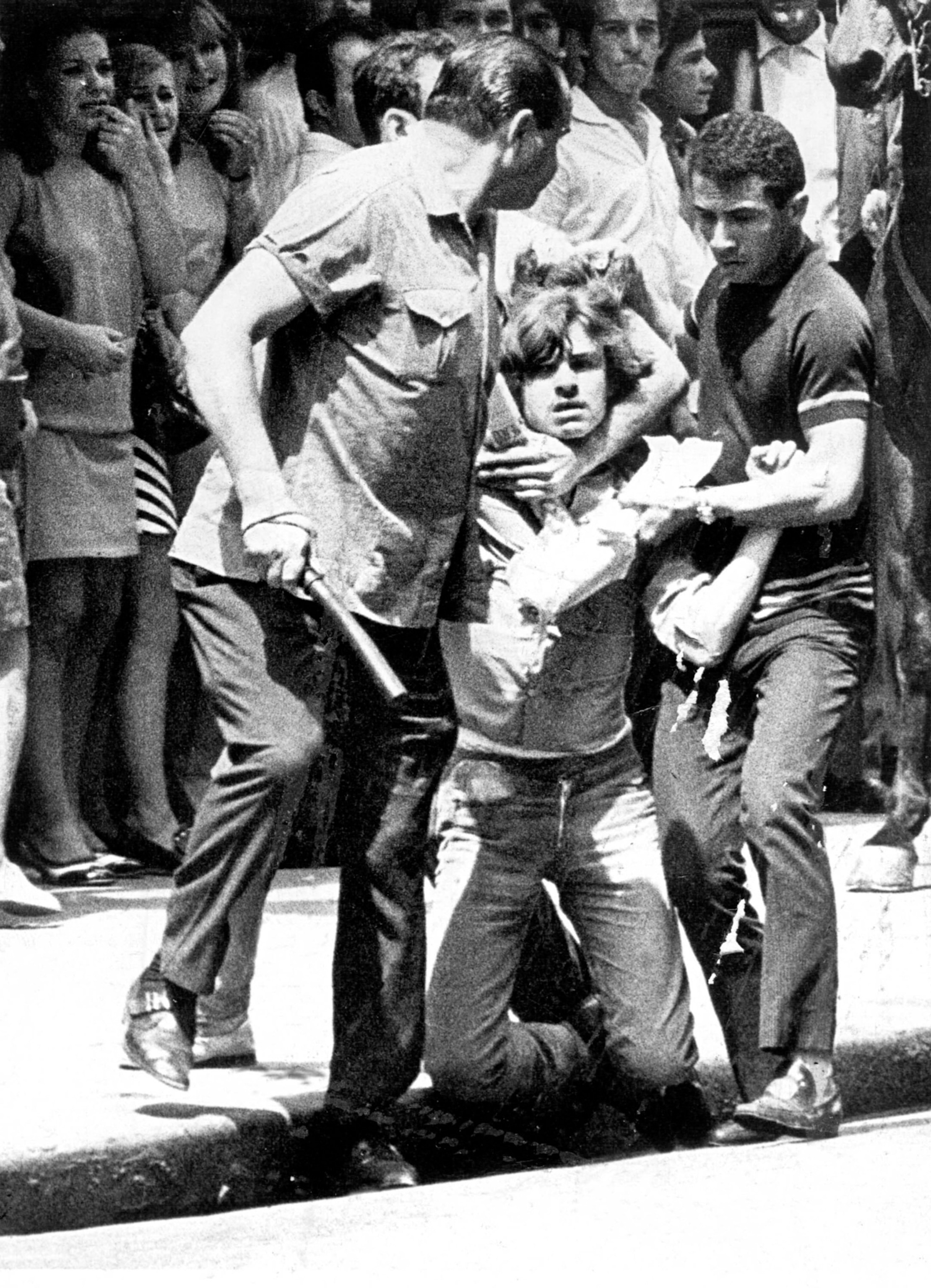

That slight fueled Brazil’s pursuit of an independent foreign policy, with a distinct anti-American turn. This was the Cold War, and the pivot set off alarms among an increasingly restive military, which maneuvered to contain the left-leaning president João Goulart. Congress pushed back, nudging Brazil further toward a constitutional crisis. On March 31, 1964, tanks were rolling in the streets. Goulart was out and martial law was in, with the blessings of U.S.

By the brutal standards of South American tyrants, Brazil’s 21 years of military rule might seem almost mild. In 2014, the National Truth Commission documented 434 casualties—counting those who were murdered or went missing—under five successive military rulers. As many as 2,000 people were tortured. By contrast, the Chilean dictatorship killed or “disappeared” some 3,000 dissidents, imprisoning another 38,000, while an estimated 10,000 to 30,000 were killed or went missing during Argentina’s savage “Dirty War.”

Yet the abduction and murder of Rubens Beyrodt de Paiva was a dire turn in what would become Latin America’s longest lasting military dictatorship.

Life under the hardline Brazilian military regime

By the time Paiva was abducted, the generalissimo in charge was Emílio Garrastazu Médici, the third of five military men to run the country, and the hardest of the regime’s hardliners.

The junta’s first leader, Humberto Castello Branco, came to power promising to restore democracy. The second, Arthur Costa e Silva, spoke of “humanizing the revolution,” then defenestrated congress by presidential decree, and succumbed to a fulminating stroke in 1969.

(Are these the last days of Brazil's realm of hidden wonder?)

Médici was elected that year by a closely chaperoned legislature, which the junta had hastily reconvened to add a sheen of legitimacy to their anointment. He took charge amid increasing unrest with no qualms about imposing authoritarian fiat. His wily finance minister, Antonio Delfim Netto, goosed growth with generous spending, a gusher of foreign investment, and easy money from international lenders eager to cash in on the Brazil bonanza.

The result was Brazil’s armed forces at peak hubris, emboldened by the so-called “Brazilian Miracle” (five straight years of unprecedented economic growth), the glories of a third World Cup victory, and the United States-led Cold War against global communism.

Médici oversaw the harshest crackdown on democratic liberties to date, including blanket press censorship. When newspapers were not set ablaze or shut down outright, censors lurked in newsrooms to ink out inconvenient truths. Dozens of journalists were jailed or murdered.

These were Brazil’s “Years of Lead,” best known for the nationwide dragnet Médici cast to capture and kill leftist opponents of the regime. The most strident militants took up arms, robbing banks and kidnapping high profile officials—including U.S. ambassador to Brazil Charles Elbrick in 1969—for ransom.

Why Paiva's story in 'I'm Still Here' resonates

Paiva was no bomb thrower. A moderate leftist, he had been stripped of his congressional mandate when the miliary took power and steered clear of militant politics ever since. Rather, he was a middle-aged family man, a successful civil engineer, and a well-heeled member of Brazil’s bien pensant. His offense, ostensibly, was to have served as a go-between for Brazilian political exiles in Chile corresponding with relatives and colleagues back home.

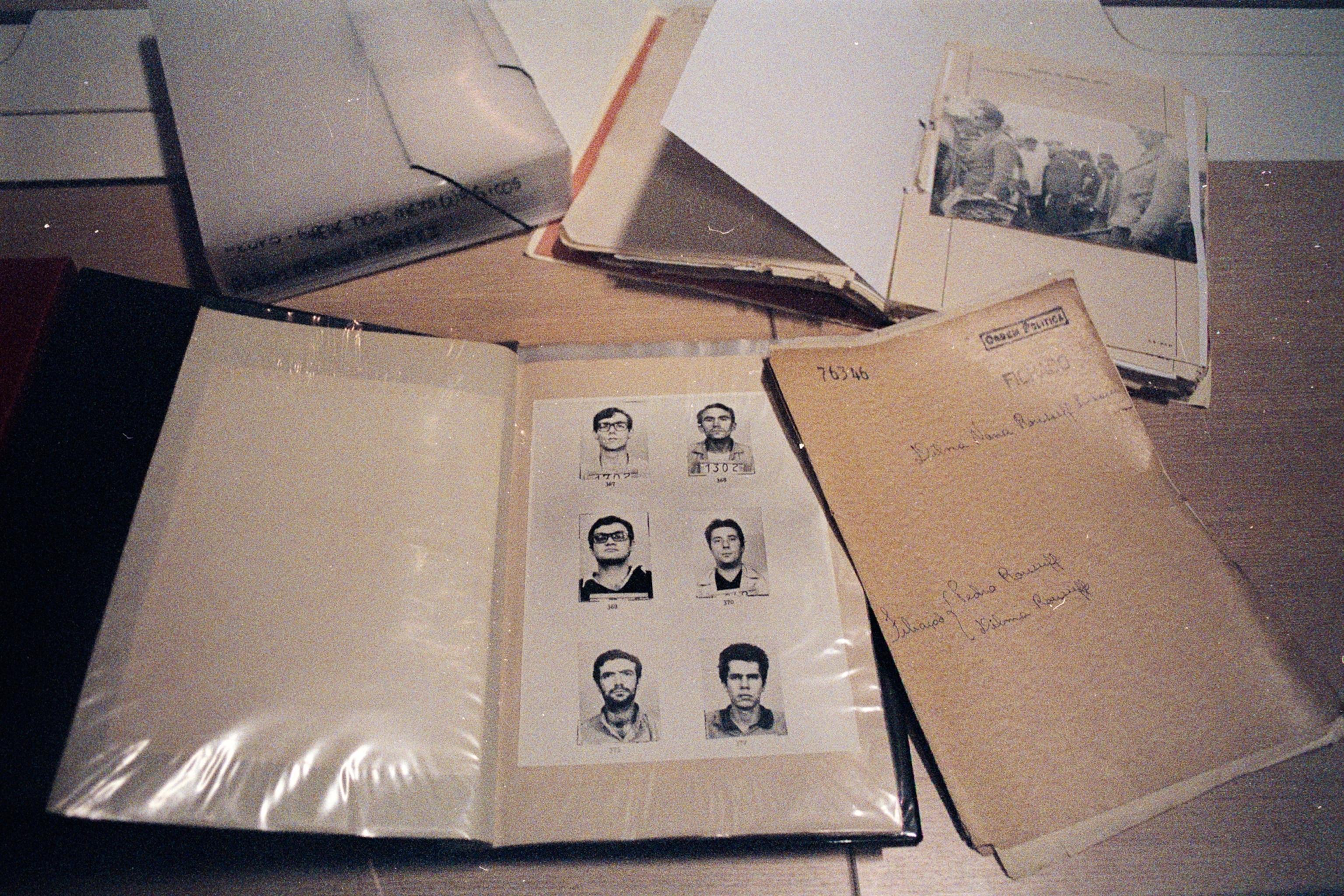

Paiva’s remains were never found, nor has anyone been held to account for his murder or forced disappearance— thanks largely to the blanket amnesty for political crimes enacted in 1979.

But the constant drip of pressure from Eunice Paiva helped corrode the moral high ground of a regime convinced of its mission to rescue the country from godless insurrectionists. Without her decades of perseverance and the paper trail she left in her unrelenting campaign to find her husband, Brazilians might never have seen through the flimsy official version of the case—that Paiva was purportedly abducted by terrorists—much less imagined that the state would one day own its role in his violent death.

(How Mussolini led Italy to fascism—and why his legacy looms today.)

Instead of bowing to unyielding strongmen, Eunice carried on, earned a law degree and went on to defend the rights of Indigenous people in harm’s way.

All this makes for compelling cinema, but why tell this tale now? Brazil’s dictatorship ended in 1985, three generations of moviegoers ago. “Young Brazilians know nothing about the military period except what they read in books and hear from their elders,” says Octavio Amorim Neto, a political analyst and scholar of military history at the Getulio Vargas Foundation.

Director Walter Salles took the cue. He started researching the film seven years ago, just as Brazilian politics took an abrupt jag to the right and faith in democracy began to slip.

This troubling turn in contemporary Brazilian politics is latent, but never explicitly mentioned in the film. Yet the public response to I’m Still Here—already Brazil’s highest grossing film at the home box office and its biggest earner abroad in 22 years—sends a strong message: While the ghosts of dictatorship may still hover, Brazilians aren’t about to look away.