Emily✨'s Reviews > The Strawberry Statement: Notes of a College Revolutionary

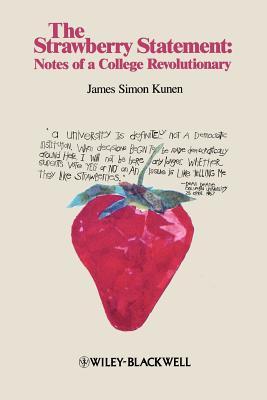

The Strawberry Statement: Notes of a College Revolutionary

by

This diary-format eye-witness look at the rebellion of Columbia University students in 1968 was a lot more interesting than I expected it to be. It helped that the author's writing voice was actually a delight-- Kunen was hilarious and cynical and I laughed out loud quite often, especially in the first half.

I didn't know anything specifically about the protests at Columbia, though of course I knew that 1968 was a year of great social upheaval in the US in general. I chose to read The Strawberry Statement for a more general look at student protesting fifty years ago and compare it to the current social situation.

What I found is that... things haven't really changed much. Or maybe they've even gotten worse? It was a trip to see the same sentiments that feminists and anti-racists write think-pieces about today being written by a 19-year-old in 1968. Much of this book could easily be applied to contemporary events.

The format of this book isn't the best. As it is a published diary, there is some context missing from much of the events described; possibly if I knew more about the specific events I wouldn't have felt so lost. Instead, I was confused about what exactly was happening, especially in the second half of the book, when Kunen lost some of his clear-headed-ness and became noticeably confused, apathetic, and depressed in turns. Still, since it was more interest in the general sentiment of the time, rather than research into the specifics, I didn't mind feeling confused. I was still interested in Kunen's ponderings. I also read the book in short bursts over almost a month, as the author himself suggests it is best consumed in small doses due to the general disorganization of his thoughts.

Kunen paints quite the picture of the reactions of school administration, fellow students, police, media, and general citizens to the rebelling Columbia students. It was incredible to read about police brutality at peaceful protests and marches-- including an incident when NYPD purposefully barricaded the Columbia campus to pen in the student protesters, covered their badges with tape, then proceeded to use their bully clubs, rubber bullets, and tear gas to round up and arrest the students. Kunen himself was arrested in this instance.

I can't say how Kunen's writings on race relations of the time were received when this was first published, but there was certainly some problematic terminology by today's standards. Kunen often refers to "the blacks", and often in differentiation from "the students" indicating that none of the students were black. Later in the book there is mention of black students, leaving the reader to wonder whether black students were part of the protests and what they thought of the whole situation. In other words, Kunen's account is not very intersectional in scope; but, then, it is a personal diary, not a thoroughly researched exposé. There was also a metaphor comparing the Viet Cong to cockroaches which, while not specifically pejorative, certainly was in bad taste.

I've noticed that a few different reviewers have concluded that The Strawberry Statement demonstrates that student protesters don't know what they're doing. I'd say, duh, of course they don't, who ever knows what they're doing? But protesters don't have to know everything to know that what they're witnessing is wrong, and to know that they can do something about it. Even when Kunen becomes apathetic, it is out of frustration with the different factions and the infighting that hinders any real progress, not because he has decided that there's nothing worth fighting for.

I think one of the biggest take-aways from this book is that there's nothing new about criticizing the American government. "Make America Great Again"? And when exactly was it great before? There are problems running deep in this country, and pointing them out doesn't make you an "SJW", "snowflake", or "commie" today any more than it did in 1968, or 1908, or 1861, and on and on. As the saying goes, if you're not angry, you're not paying attention. Though it's somewhat disheartening to see how little has changed since 1968, I think it's clear that the movements have grown and have encompassed more and more people over the generations. (It seems to me that) there are more different kinds of people talking about and caring about social change today than in the past, which provides some hope for an eventual tipping point, hopefully not too long in the future.

[All bolding is mine]

by

Emily✨'s review

bookshelves: theme-social-justice-activism, collection-non-fiction, genre-historical, genre-bio-memoir, theme-america, rating-3-star, access-library

Aug 07, 2018

bookshelves: theme-social-justice-activism, collection-non-fiction, genre-historical, genre-bio-memoir, theme-america, rating-3-star, access-library

Isn’t it singular that no one ever goes to jail for waging wars, let alone advocating them? But the jails are filled with those who want peace. Not to kill is to be a criminal. They put you right into jail if all you do is ask them to leave you alone. Exercising the right to live is a violation of law. (61)

[My mother] points out that neither Gandhi nor Thoreau would have asked for amnesty. I admit I haven’t read them. But Gandhi had no Gandhi to read and Thoreau hadn’t read Thoreau. They had to reach their own conclusions and so will I. (29)

This diary-format eye-witness look at the rebellion of Columbia University students in 1968 was a lot more interesting than I expected it to be. It helped that the author's writing voice was actually a delight-- Kunen was hilarious and cynical and I laughed out loud quite often, especially in the first half.

I can assure you that the Columbia action cannot be dismissed as an overgrown panty raid, a manifestation of the vernal urge. It lasted too long; participants endured hardship, and worse, boredom, conditions through which collegiate fetishistic folly could never sustain itself. (150)

I didn't know anything specifically about the protests at Columbia, though of course I knew that 1968 was a year of great social upheaval in the US in general. I chose to read The Strawberry Statement for a more general look at student protesting fifty years ago and compare it to the current social situation.

The moderator [...]said that what [adults] are doing today is paying the penalty for years of permissiveness, which is true, if permissiveness means raising kids to think and not obey any authority that happens to come stomping along.

All concurred that we students “should be busy studying to be leaders instead of carping about things.” (57-58)

What I found is that... things haven't really changed much. Or maybe they've even gotten worse? It was a trip to see the same sentiments that feminists and anti-racists write think-pieces about today being written by a 19-year-old in 1968. Much of this book could easily be applied to contemporary events.

In America you shouldn’t have to worry about police busting into your apartment and beating you up. I specifically remember seeing a TV show around thirteen years ago about an immigrant couple who still had their old country fears and thought the mailman was a cop coming to take them away. They weren’t confused; they were just ahead of their time. (79)

The format of this book isn't the best. As it is a published diary, there is some context missing from much of the events described; possibly if I knew more about the specific events I wouldn't have felt so lost. Instead, I was confused about what exactly was happening, especially in the second half of the book, when Kunen lost some of his clear-headed-ness and became noticeably confused, apathetic, and depressed in turns. Still, since it was more interest in the general sentiment of the time, rather than research into the specifics, I didn't mind feeling confused. I was still interested in Kunen's ponderings. I also read the book in short bursts over almost a month, as the author himself suggests it is best consumed in small doses due to the general disorganization of his thoughts.

Most people agree that there are good cops and bad. But everybody assumes that there have to be cops, that there always have been. I have no plan for abolishing police forces, but I do think people should consider that police are not the most natural thing in the world [...]It seems strange to me that a few men should be taken from the community and given the job of watching out for it. […H]e’s got his club and his gun and everybody seems to think that’s the way it’s supposed to be. (140)

Commenting on the importance of student opinion to the administration, Professor Deane declared, “Whether the students vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on an issue is like telling me they like strawberries.” (121)

Kunen paints quite the picture of the reactions of school administration, fellow students, police, media, and general citizens to the rebelling Columbia students. It was incredible to read about police brutality at peaceful protests and marches-- including an incident when NYPD purposefully barricaded the Columbia campus to pen in the student protesters, covered their badges with tape, then proceeded to use their bully clubs, rubber bullets, and tear gas to round up and arrest the students. Kunen himself was arrested in this instance.

Think twice before you pour your stinking bloody money into more weapons because people are hungry and we won’t let you. We need good schools and houses for people to live in and it could be done and we’re going to make this country do it. (94)

I can't say how Kunen's writings on race relations of the time were received when this was first published, but there was certainly some problematic terminology by today's standards. Kunen often refers to "the blacks", and often in differentiation from "the students" indicating that none of the students were black. Later in the book there is mention of black students, leaving the reader to wonder whether black students were part of the protests and what they thought of the whole situation. In other words, Kunen's account is not very intersectional in scope; but, then, it is a personal diary, not a thoroughly researched exposé. There was also a metaphor comparing the Viet Cong to cockroaches which, while not specifically pejorative, certainly was in bad taste.

Social progress is slow. It’s practically nonexistent. We’re about where we were 10,000 years ago. But you have to try to make it go fast so that it will go slow at all. (102)

I've noticed that a few different reviewers have concluded that The Strawberry Statement demonstrates that student protesters don't know what they're doing. I'd say, duh, of course they don't, who ever knows what they're doing? But protesters don't have to know everything to know that what they're witnessing is wrong, and to know that they can do something about it. Even when Kunen becomes apathetic, it is out of frustration with the different factions and the infighting that hinders any real progress, not because he has decided that there's nothing worth fighting for.

But sadness is not despair so long as you can get angry. And we have become angry at Columbia. Not having despaired, we are able to see things that need to be fought, and we fight. We have fought, we are fighting, we will fight. (6)

I think one of the biggest take-aways from this book is that there's nothing new about criticizing the American government. "Make America Great Again"? And when exactly was it great before? There are problems running deep in this country, and pointing them out doesn't make you an "SJW", "snowflake", or "commie" today any more than it did in 1968, or 1908, or 1861, and on and on. As the saying goes, if you're not angry, you're not paying attention. Though it's somewhat disheartening to see how little has changed since 1968, I think it's clear that the movements have grown and have encompassed more and more people over the generations. (It seems to me that) there are more different kinds of people talking about and caring about social change today than in the past, which provides some hope for an eventual tipping point, hopefully not too long in the future.

There used to be a dream for America. You know, the American dream? America was going to be different. Free. Good. Free and good. Of course they blew it right away. As soon as the Puritans came over they set up religious laws. But at least they clung to the dream. Until now. Now no one hopes for America to be different. I guess it was the dream that ruined the dream. People became convinced it was true, so they never made it true. People think the U.S.A. (a great-sounding, nice, informal name) is special, so we can do anything and it’s okay (an American expression). People should wake up and dream again. (64)

[All bolding is mine]

Sign into Goodreads to see if any of your friends have read

The Strawberry Statement.

Sign In »

Reading Progress

July 13, 2018

–

Started Reading

July 13, 2018

– Shelved

August 7, 2018

– Shelved as:

theme-social-justice-activism

August 7, 2018

– Shelved as:

collection-non-fiction

August 7, 2018

– Shelved as:

genre-historical

August 7, 2018

– Shelved as:

genre-bio-memoir

August 7, 2018

– Shelved as:

theme-america

August 7, 2018

–

Finished Reading

July 22, 2019

– Shelved as:

rating-3-star

November 21, 2019

– Shelved as:

access-library